via Interpretive elements for exhibit Vanishing Ice: Alpine and Polar Landscapes 1775-2012

Author Archives: eliswsommer

Grant Report Narrative on Animating the Kress Collection

This was submitted to the Samuel H. Kress Foundation for their support of the project to produce animated videos of works in the Kress Collection.

Animating the Kress Collection Grant Report

The El Paso Museum of Art used a Digital Resources grant from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation to produce a set of short animated videos of paintings drawn from the Museum’s European collection. The grant period ran from 2014-2016. The project was intended to bring these core paintings to life, help contemporary audiences find connections to old art, to give teachers an innovative teaching tool, and to impart information in engaging ways.

In order to realize this project, the Museum contracted with Dr. Sabiha Khan, currently a tenure-track faculty member in digital media at the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), and offered paid internships to students with skills in digital and animated media. Dr. Khan managed the interns, who produced the animations, and she handled all audio and final editing of the videos. Dr. Elisabeth Sommer, Education Curator for EPMA, did the research for the audio narrative, which was crafted from interviews with Dr. Khan, and assisted with editing content. She also managed the project for the Museum.

The basic goals of the project were to engage new audiences with old art, provide tools for classroom use, particularly for schools not able to travel to the Museum, and to promote interest in the Kress Collection. Consequently, the videos are aimed at non-experts, from middle-school age to adults. The project was also intended to provide training opportunities for undergraduate, and recently graduated, students in digital media.

The following evaluation results from the interns indicate success in reaching this goal. When asked whether the internship provided “practical experience…in media production in a museum/non-profit context” 60% agreed and 40% strongly agreed. The percentage breakdown was the same for the statement that the “internship activities were challenging and stimulating” and for whether they would recommend the internship to others. To the question of whether the internship had resulted in “a greater understanding of the concepts, theories, and skills of producing media in a museum/non-profit context” 80% strongly agreed, while 20% agreed. The percentages were identical for the internship having provided “sufficient learning opportunities.”

Written comments from the evaluations provide additional gratifying insight. When asked whether the internship met their expectations, students responded with the following: “Yes, it actually exceeded my expectations. I did not think I would learn as much as I did;” “It taught me a big deal [sic] about how to develop and follow a workflow when working with animation;” “It was the first time I really had to do something as a group in the real world and that experience has been extremely valuable.” When asked to summarize the strengths of the internship one student stated that “it helped me innovate and create independently. It pushed me to learn more about art, especially the history of each painting, art era, etc. It motivated me to explore different types of animation and what I could do with each animation software.” Another student observed that the “supervisors’ dedication and passion towards the pieces of art is evident, which helps you understand the artist’s life and work, hence making [it] easier and more interesting to develop creative ideas.”

Evaluations of the videos also indicate general success in meeting the goals of engaging audiences with “old master” European paintings and raising interest in Kress Collection at EPMA. Evaluations of the first and second sets of videos (eight total) were given to three different sets of evaluators, members of a high school class in digital media, students in an introductory Museum Studies class at UTEP, and members of UTEP’s Art History Association. The evaluation included the following questions: 1. “Did the animation(s) increase your interest in or curiosity about the artist?” 2. “Did the animation(s) increase your interest in or curiosity about the painting?” and 3. “Are you more likely to visit the museum’s European painting section after watching the video(s)?” The average percentages for each question and each group are presented in the graph below.

| Question 1 (artist) | High School | Art History Assoc. | Museum Studies |

| Definitely | 31% | 70% | 49% |

| Somewhat | 55% | 30% | 37% |

| No | 14 % | NA | 15% |

| Question 2 (painting) | |||

| Definitely | 44% | 70% | 50% |

| Somewhat | 38% | 30% | 45% |

| No | 18% | 0% | 5% |

| Question 3 (visiting) | |||

| Yes | 32% | 80% | 55% |

| No | 26% | 0% | 14% |

| Maybe | 42% | 20% | 31% |

Although we would, of course, have liked to see a larger percentage of the high school evaluations fall into the “definitely” and “yes” categories, given the fact that these students were not predisposed to be interested in art at all, let alone the art of the past, an average of ¾ or more outside of the negative category seems a good sign. One of these students also commented that “It was like finding hidden Easter Eggs and in a way you really learned about the artist by the details that were worked into the painting.” That sort of engagement was exactly what we had hoped for.

These evaluations (except for those given to the Art History Association), were administered during the final editing process and contained additional questions, such as whether anything was confusing, and whether the length of the video was appropriate. Answers to these questions provided feedback that was useful in creating the final edits. In addition to technical comments, we discovered, somewhat to our surprise, that the students felt the videos, originally aimed at 4-5 minutes in length, should be longer, and contain more information (dates, etc.). We have also developed a survey for area art teachers, a copy of which is attached to this report, which has gone out through Survey Monkey along with links to the complete set of videos. We will send those results as soon as we have them.

Aside from the formal evaluations, the first eight videos have garnered positive comments from those who have seen them on the local public television station, where they have been shown on a rotating basis. The first four have also been uploaded to the Digital Wall at the El Paso Museum of History, and to an avatar at the new Border Medical building. The remaining videos should be uploaded soon.

One unanticipated result of the project has been the opportunity to pull together all the available information on the selected paintings, and to dive deeply into each one. Among other insights, there is a strong case for the identification of the Anthony van Dyck portrait as that of Clara Brant Foument, and a much clearer understanding of the context of the artworks, especially those by Botticelli and his workshop, Filippino Lippi, and the Sienese pieces. This information has the potential to be used to engage visitors in new ways and support a more extensive use of the collection in the classroom.

During the two- year grant cycle, the team encountered challenges and learned lessons that could benefit similar projects. Most of the difficulties we faced had to do with the logistics of producing a large number of animated videos, each of which varied enough to make creating a clear production template problematic. For example, some of the paintings lent themselves easily to animation, that is, the artwork offered a lively canvas for telling its story without a great need for additional images. Other paintings, such as the portraits, were more static and needed external images to bring the video to life. This resulted in a lot of time spent identifying additional appropriate images, and a need for larger video files needed to accommodate outside high-resolution images.

The need for outside images had been anticipated in the grant budget, however obtaining permission from institutions proved difficult for two reasons. The turnaround time for responses from various museums was generally quite slow, and made it hard to proceed with the animation within our time frame. Additionally, the policies of most institutions have not caught up with the digital revolution, and are crafted primarily to accommodate the use of images in exhibitions for a limited term. As these videos will be based on the web, it is impossible to edit them in order to remove images after a short-term lease. Because of these factors, almost all outside images were taken from Creative Commons sources.

Working with student interns also produced some bumps along the way. They needed more hands-on management and their work needed more intensive editing (at least initially) than anticipated. This resulted from weakness in their time management, varying degrees of skills, and, in some cases, competition from other paid work. As the project took shape, the team also came to realize the need for multiple skills, including a sense of storyline, imagination, hand-drawing, specific types of editing, as well as animation itself. In addition, we were not able to retain the same set of interns over the course of the project. This meant training new interns in the basic approach to creating the videos, as well as how to work together.

As one of the interns observed in the evaluation, one potential solution to some of the difficulties would have been to divide the tasks for each video by skill, rather than by narrative section, which is what we did for most of the videos. Recruiting interns for specific skills, such as hand-drawing or editing abilities, might also help the process run more smoothly. The intern also commented that meeting more regularly as a group, s/he felt, would have helped keep the creative energy strong. Given the number of individuals involved in the project, scheduling meetings that worked for everyone was difficult, but is something that would probably have benefitted the project. Despite these challenges, the team was, and is, very proud of the resulting videos. Links to all the videos are embedded below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x87GXAqprPU&t=1s

Fontana

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_99yok3ACxM&t=1s

Strozzi

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SGcaUoJq55E&t=23s

Van Dyck

Canaletto, Crespi, Rigaud, Gentileschi, Sustris, Dossi, da Carpi, Lotto, Lippi, Botticelli, Sano di Pietro, Osservanza Master

Grant Report Narrative for Art Comes to Life program

This grant report was submitted to Humanities Texas.

Narrative Report on Art Comes to Life!

El Paso Museum of Art

September 27, 2014

With the support of a matching mini-grant from Humanities Texas (#2014-4611) for $1500 toward a total project cost of $3990, the El Paso Museum of Art was able to provide Art Comes to Life! to the El Paso Community with the following results:

- Presenters

Dennis Thompson, Kelly Watson, and Riley Watson, members of Historic Interpretations Inc. out of Raleigh, N.C., made ongoing presentations throughout the day from 11:00 to 4:00. Unfortunately Jeremy Clos was unable to participate due to illness. As there was insufficient time to develop a new interpretive character, his place was taken by Jaclyn Bell, who has media expertise and video-taped the performances. They saw a total of 254 visitors over the course of the event, with the potential for a much larger virtual audience through use of the videos taken both by Historic Interpretations and by one of our partners in a Kress Foundation animated video project.

- Major Accomplishments

Art Comes to Life! successfully engaged visitors with European “old master” paintings by contextualizing them. The historic interpreters were able to help people connect the static images with the individuals depicted and with life during the period in which the artwork was made. They also gave insight into the artists and their work. Children in particular were full of questions and fascinated by the costumes and being able to talk with a “painting.” In the long term, capturing the interpreters and the interaction on video will allow them to be utilized in augmented reality, and potentially in the animated video project.

- Quality of Presentation

All the presenters were masterful in engaging visitors and imparting information. Riley Watson stood out with her ability to work with the younger audience. Her youth made her especially approachable. She never broke character, and, as a credentialed actress (member of SAG) she drew people into the world she was interpreting. She also used the dice game to attract visitors to her station.

- Dialogue

The overall success of the event was driven by the use of dialogue between the interpreters and visitors. At several times throughout the day you could observe groups clustered around the interpreters, having lively conversations with them. Afterwards the interpreters remarked on the quality of their interaction with children and were impressed with how interested and intelligent they were. Visitors generally left smiling, and one visitor in particular asked if we were going to do this again and declared it to be a fantastic experience. Photographs of the event illustrate the level of interaction and the make-up of the audience.

- Recommendations

I would certainly recommend Historic Interpretations Inc., particularly if an institution wants to interpret a number of different time periods. They are fully capable of bringing to life the sixteenth through the early nineteenth centuries.

- Print Materials

Humanities Texas was credited in all printed materials and publicity distributed regarding this event including the following: Official Press Release, Fall 2014 Members’ Update, October 2014 Events Calendar

- Suggestions

I have no suggestions for improvement in the mini-grant program and am grateful to Humanities Texas for providing funding to help make this event possible. Please find attached documentation of the event for your files.

Final Descriptive Report for NEA Grant (performing arts section)

This is my section of the grant report submitted to the National Endowment for the Humanities in 2017. The grant supported performing arts programming connected to the Modern Masters: Selections from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum series.

Part I: Project Narrative

- Activities Supported by the award and accomplishments

The El Paso Museum of Art utilized $30,000 of the $65,000 NEA grant to cover part of the final $150,000 lease fee required by contract with the Guggenheim Museum for the series Modern Masters: Highlights from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Support from other sources helped pay for the remainder of the lease fee as well as for the purpose of providing every visitor to the Museum free access to the Guggenheim series. The following four exhibitions were presented: Paul Cézanne and Pablo Picasso (Birth of Cubism) (from 3 October 2014 to 1 February 2015); Vasily Kandinsky and Franz Marc: Expressionism and Der Blaue Reiter (from 13 February to 31 May 2015); Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes: The School of Paris (from 5 June to 24 September 2015); and Marc Chagall: The Green Violinist (from 2 October 2015 to 29 January 2016).

The El Paso Museum of Art used $35,000 of the $65,000 grant to support performing arts programming in conjunction with the Modern Masters series. The performing arts portion of the series programming consisted of partnership performances with the El Paso Opera, the El Paso Symphony Orchestra, and El Paso Pro-Musica, a chamber music organization. These performances connected with the loan cycles Vasily Kandinsky and Franz Marc: Expressionism and Der Blaue Reiter, Robert Delaunay and Albert Gleizes: The School of Paris, and Marc Chagall: The Green Violinist.

The second of two performances by El Paso Pro-Musica was slated to connect with the final cycle, Pablo Picasso: Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit. Unfortunately, the Guggenheim Museum pulled out of the loan series following the Chagall cycle. The NEA gave permission to use those funds to support programming for the Museum’s exhibit Posting Picasso (June 26-September 11, 2016). On-site performances by all participating organizations were free and open to the public.

The performance series allowed the Museum to spotlight connections between the visual and performing arts. Visitors who attended events during the series were encouraged to experience the ways in which artists crossed disciplines, and/or were inspired by other types of art and artists. The series also paired well with the partnership that we have with the El Paso Symphony’s afterschool program, The Tocando Music Project, in which students visit the Museum twice a semester for lessons that explore the connections between art and music.

- Were you able to carry out all approved project activities?

No: Two more exhibitions, respectively presenting two geometric works by Kandinsky and one monumental still-life by Picasso, were originally planned, but these had to be canceled when the Guggenheim unilaterally cancelled the contractual agreement.

However, we were able to carry out all performing arts programming, even though the Guggenheim pulled out of the loan agreement early. The willingness of the NEA to approve the use of funds to support programming for the Museum’s Posting Picasso exhibit enabled us to complete all planned programs and partnerships.

- Who were the key artists and partnering organizations, and what was the nature of their involvement?

The main exhibition partner was the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Curatorial staff from EPMA supplied installation design plans to the Guggenheim for their approval. Educational staff from the Guggenheim provided in-gallery didactic text for approval by EPMA, which had them translated into Spanish for our large Hispanic audience. Shipping arrangements were agreed upon by the two museums, and the couriers required by the Guggenheim were provided with hotel and per diem by EPMA.

The El Paso Opera staged an immersive, multi-media version of Vasily Kandinsky’s Der Gelbe Klang, using music commissioned for the performance from composer Roger Ames. Lighting Designer, Barry Steele, created an evocative environment using video clips and colored light to reflect Kandinsky’s belief in the connection between color and sound. Performances were preceded by an in-gallery talk by Opera Director, David Grabarkewitz, and El Paso Museum of Art Education Curator, Dr. Elisabeth Sommer, covering Kandinsky’s color theory, and the cultural context of his opera (1909) and his artwork.

The El Paso Symphony Orchestra presented a luncheon performance and talk focused on the connection between musicians and artists in early 20th-century Paris. The Symphony’s Artistic Director, Bohuslav Rattay, Resident Conductor, Andy Moran, and the Museum’s Education Curator, Dr. Elisabeth Sommer, used images of Robert Delaunay’s Circular Forms (1930), and Albert Gleizes’ On Brooklyn Bridge (1917) to explore the ways in which art and musical forms reflected similar concerns with modernization and urban life, both embracing and reactive. Harpist Hope Cowan performed Claude Debussy’s Maid with Flaxen Hair (1910), and Marcel Grandjany’s Barcarole (1922). Flutist Melissa Abeln-Colgin performed Arthur Honegger’s Danse de la Chevre (1921) and Claude Debussy’s Syrinx (1913).

The Museum also partnered with the Symphony to host a pre-talk prior to their September concert featuring Czech pianist Veronika Bömová, playing Ravel, and a performance of Igor Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Artistic Director, Bohuslav Rattay, Resident Conductor, Andy Moran, the Museum’s Senior Curator, Dr. Patrick Shaw Cable, and Education Curator, Dr. Elisabeth Sommer, made connections between the art of Delaunay and Gleizes, and the cultural context that produced Stravinsky’s revolutionary ballet.

El Paso Pro-Musica launched a new initiative, the Young Artists Development series, in conjunction with the exhibition Marc Chagall: The Green Violinist. Violinist Nikita Borisevich and pianist Margarita Loukachkina, students at the Peabody Institute, performed music by Igor Stravinsky and Sergei Prokofiev, both friends of Chagall. The concert took place at the Museum. The young musicians also joined Pro-Musica Artistic Director, cellist Zuill Bailey, for an interactive in-gallery presentation to visiting school groups. In August, Mr. Bailey and pianist Dominic Dousa, performed music by Picasso’s contemporary and fellow Spaniard, Manuel de Falla.

- Discuss the extent to which you achieved the NEA primary outcome identified in your application.

The primary outcome identified in our application was “engagement.” The four Guggenheim series exhibitions allowed EPMA to bring to El Paso major works of twentieth-century European modernism, which the majority of our visitors have never seen. A crucial aspect of engagement for the project was to make every exhibition free to members and non-members alike, which financial support allowed EPMA to accomplish. EPMA also used ancillary financial support to provide bus scholarships to enable broader engagement with the exhibits on the part of area school districts. These scholarships were targeted in particular for schools in the outer rural districts.

Engagement was enhanced by the performing arts programming created around the exhibitions. Two of the musical performances in particular gave evidence of strong engagement. In the case of the El Paso Opera’s presentation of Der Gelbe Klang, the performance was recorded on video and posted on the Museum’s Facebook page.

In addition to a formal concert, El Paso Pro-Musica’s first guest artists in its inaugural Young Artists Development series, visited the museum with Zuill Bailey for an out-reach presentation. The musicians engaged students in a discussion of Chagall’s connection to the violin, and ways in which music can express the feelings an artwork evokes. Students responded enthusiastically to being able to listen to music while looking at the original artwork. This experience had an impact on the young artists as well. In a televised interview, Ms. Louchachkina commented that “The children that we’ve played for, they’ve been so smart, so engaging, their imaginations just sparkling.”

The patrons of the El Paso Symphony also responded enthusiastically to the programs featuring pre-concert talks at the Museum. Two patrons put their thoughts in writing as follows: “I thoroughly enjoy attending the functions at the Museum followed by the Symphony concert. They provide me a deeper appreciation for the art and enhances my experience at the concert.” “I am a longtime subscriber of the Symphony… and I no longer can attend every concert, but I never miss these programs. It’s a wonderful way for me to get to hear the music and see the art.”

- Beyond the project’s direct accomplishments, what was the impact on-or benefit to-your organization, your discipline/field, and/or your community?

The Guggenheim exhibition series fostered greater understanding and appreciation among our audiences for the work of major European masters of twentieth-century modernism. By offering free access, the Museum underlined its commitment to bringing great art to all of its community, regardless of financial status. Finally, the exhibitions instilled a sense of local pride in the Museum, the City of El Paso to which the Museum belongs, and the cultural community. This was manifested, in part, by extensive coverage of the exhibit in local publications.

In terms of the performing arts programs, the project strengthened our institutional partnerships, in particular with the El Paso Symphony Orchestra and El Paso Pro-Musica. It allowed us to see what is possible when we develop programming that crosses art disciplines. Working with the Symphony to connect art and music though concerts and talks, helped to support and invigorate the Art Beats initiative, which launched in the winter of 2014. Art Beats is the Museum’s partnership program with the Symphony’s Tocando Music Project (based on El Sistema in Venezuela). During the run of the NEA performing arts grant, the students in Art Beats benefitted from the relationship we built with the Symphony. The visiting young artists from Pro-Musica also visited the Tocando classroom. This helped strengthen the connection with the Art Beats lesson that focused on the Chagall piece.

Part IIA: Project Activity

Number of Exhibitions 4

Number of Concerts/Performances/Readings 8

Number of Arts Instruction Activities 10

Part IIB: Individuals Benefitted

“In-person” Arts Experience

- Adults: 63,380

- Children/Youth 17,342

- Total 80,722

Part IIC: Population Descriptors

Race/Ethnicity:

H-Hispanic or Latino

W-White

Age Ranges

- Adults (25-64 years)

Underserved/Distinct Groups

- No single underserved/distinct group made up more than 25% of the population directly benefitted.

Grant Report Narrative for Community Catrina Project

This is the grant report submitted to the Texas Commission on the Arts for the 2016 funded Community Catrina project.

TCA Community Catrina Project Report Narrative

Audience Info:

Total persons served directly: 90

Number of youth served: 79

Number of artists directly involved: 1

Ethnic Breakdown: 90% Hispanic; 5% Black; 5% Caucasian

Cultural Tourism:

Did grant promote cultural and/or heritage tourism No

Did you capture zip codes of attendees No

Personnel Info:

Artists who received a fee: 1

Non-artist volunteers: 1

Full-time personnel: 3

Narrative

How did this grant benefit your organization and/or community? (400 words)

The Community Catrina project allowed EPMA to engage with an underserved audience, to enrich existing community partnerships, and to partner with a fellow city agency. Although the South El Paso community is within easy reach of the Museum, its residents rarely cross the institution’s threshold. EPMA has sought to address this through programs partnering with specific South El Paso schools, for example the long-running Neighborhood Kids program with Aoy Elementary School, and, more recently, Art Beats, with the El Paso Symphony Orchestra’s Tocando Music Project at Hart Elementary School. The Catrina project engaged both of these pre-existing partnerships, while also reaching out to attendees of the Armijo and Chuihuahuita Recreation Centers’ afterschool programs.

Making individual or family Dia de los Muertos altars allowed participants to explore their inner artist in a form with cultural significance to them. Several teenaged participants chose to honor pop stars, such as Selena and Paul Walker. Most of the younger ones honored grandparents, other relatives, or pets, including, in one case, a beloved pet turtle. Most, if not all, of the participants from the recreation center, had never had any connection to the art museum, even though it shares their zip code. The experience also gave participants the opportunity to work with a professional artist, Wayne Hilton, who inspired them and encouraged them to use their own creativity and imagination. Hilton commented that “engaging with the altar makers tryly stirred my artistic direction with the piece and the overall project.” The completed Catrina figure was unveiled in a celebration at the Museum that included the public presentation of the Mexican Consulate’s Dia de los Muertos altar, and an open house for Wayne Hilton’s Hermosos Huesos: Beautiful Bones exhibit of Catrina figures. This allowed the participants in the Community Catrina project essentially to become exhibited artists within a larger cultural context.

For the Tocando participants in particular, the project brought their families together. It also allowed the principal of Hart Elementary, who attended the celebration, to see program impact outside of the school grounds and build trust between all parties. Finally, it brought the program to the attention of the District Representative, who was also in attendance at the celebration.

Describe any anecdotal information and/or human interest stories that have occurred as a result of this grant. (400 words)

During a parent conference for the Tocando program, one mother, who had initially been reluctant to come in and talk about the program, commented that the Catrina project had given her “complete buy-in” to Tocando. She also said that it was the first time that the entire family had come together in a long while.

Another set of parents commented on how happy and engaged their child had been during the project, and particularly during the celebration when they got to show off their work. She is quite shy and tends to be withdrawn, but they said that on that evening she interacted with friends, was smiling and excited.

On a personal level, I was particularly struck by one of the participants in the very first workshop. She expressed reluctance to leave her piece so that we could use it in the large-scale Catrina. The Recreation Supervisor spoke with her, and explained that she wanted to place it on her grandmother’s headstone in the cemetery. After we showed her a photo of the maquette for the Catrina, and explained that she would get the altar back after the celebration, she was willing to leave it behind. What this said to me was that this project had brought art-making and the museum to a very personal place in this little girl’s life.

Grant Narrative for Community Catrina Project, Texas Commission on the Arts

This is the narrative for a grant request successfully submitted to the Texas Commission on the Arts in 2016. It has been edited to remove institutional information.

Information on Audience Targeted by your Proposal

Economically disadvantaged

At-risk youth

How many adults will be engaged in “in-person” arts experiences?

25-35

How many children/youth will be engaged in “in-person” arts experiences?

35-50

Ethnic Information

Ethnic breakdown of individuals to be served

85% Hispanic

05% Black

10% White

0% on all other categories

Educational Audiences Targeted

30% Pre-Kindergarten

30% K-12

40% Adult Learners

0% Higher Education

Project Description

This project will bring together members of the South El Paso community to create Dia de los Muertos altars using materials significant to them, as well as supplemental materials. The altars will be created in workshops at the Armijo Recreation Center and then be fixed to the skirt armature for a large-scale Catrina created by artist Wayne Hilton, who will also supervise the workshops. The project would take place in the fall of 2016. The Catrina body and armature will be stored at the El Paso Museum of Art, so it can be used for future community projects at other Recreation Centers.

The project is intended to engage members of the community of South El Paso in creating artwork relevant to their culture in conjunction with local El Paso artist Wayne Hilton, and to introduce them to the El Paso Museum of Art as their museum. It is also intended to deepen understanding of the history and meaning of the Catrina figure, while allowing participants to explore and celebrate their cultural heritage through personal artistic expression.

Our hope is to foster a connection between the participants and the El Paso Museum of Art, and to provide a platform for members of the South El Paso community to share their stories and creativity, and be encouraged to continue to explore their creative side.

Measurable Objectives:

- To engage a diverse portion of the targeted community (i.e. children, youth, adults, family units)

- To encourage the sharing of individual and family stories

- To “unlock” or display the creative spirit within the participants

- To introduce EPMA to the participants as a place with relevance to them

- To encourage participants to continue to explore their creative side through participation in arts-oriented activities

Cristobal Rivera, the Program Manager for Hart Elementary School’s unit of the EPSO’s Tocando Music Project, has committed to having their students participate in the Community Catrina project. The EPMA has an existing partnership program with the Tocando Music Project, Art Beats, in which they explore art interpretation.

Key Personnel:

EPMA:

Kate Loague, Community Engagement Manager

Elisabeth Sommer, Museum Education Curator

Armijo Recreation Center:

Alejandra Dominguez, Recreation Supervisor at Armijo Recreation Center

Teaching Artist:

Wayne Hilton

How does this project address the priority area (Public Safety/Criminal Justice)?

The demographic of South El Paso is heavily Hispanic, with almost 50% having little to no English. Half are immigrants, and the median household income in 2013 was $13,133. Finally, almost 70% do not have a high school degree. These demographics make for a highly at risk population.

This project will encourage family bonding, underscore a pride in community heritage, and allow participants to explore their creative potential. Its base in a neighborhood community center will connect the El Paso Museum of Art with a known alternative learning place, while the assembling, celebration, and display of the figure in the Museum will open participants to another safe place for learning and enjoyment. The Catrina project will join with two additional programs aimed at this population, the Art Beats program with Hart Elementary in South El Paso, and Paseo al Arte, a bi-lingual program in development aimed at families with pre-school children. The Catrina project’s reach will be broader, however, as it has no specific age focus.

How will you gauge the success/impact of this project?

Success will be judged against the measureable objectives through observation, assessment of participant diversity, formal evaluation by the participants, and follow-up tracking. For example, we will capture participants’ information so that we can offer them scholarships for camps and classes at the Museum, and track their response. We will also track their level of participation at subsequent creative opportunities offered by the Armijo Rec Center.

How will you ensure the artistic quality of the project will be high?

Artist Wayne Hilton began creating a series of Catrina figures in 2011. These have been exhibited at the Mulvane Museum in Topeka Kansas, the Armarillo Museum of Art, the Centennial Museum at the University of Texas El Paso, and most recently at the Midland County Public Library in Midland, Texas. This project will take place in conjunction with an exhibit of his Catrinas (Hermosos Huesos) at the El Paso Museum of Art. He has also conducted both teacher and public workshops, including a teacher workshop for the Midland ISD.

Education Curator Elisabeth Sommer has overseen a number of education initiatives that connect creative activities with Museum exhibitions. She also initiated and manages Art Beats, the partnership with the Tocando Music Project afterschool program. Prior to coming to the Museum, she taught Museum Studies at the University of Mary Washington in Virginia, and headed education departments at historic sites in North Carolina and Staten Island, N.Y.

BUDGET

Project Budget

Altar workshop supplies $600

Catrina construction supplies $900

Welding labor (skirt framework) $1300

Workshop facilitation fee $1100 (4 at $275 each)

Artist fee (creation of Catrina) $1500

Total budget $5,400

TCA Request= $5,400 (Artistic Salary of $1,500 and $3,900 Program/Exhibit Production Cost)

EPMA Match= $5,724 (Administrative Salaries, Benefits and Contracts $3,626 and Marketing Materials $2,098)

El Paso Museum of Art Audio Guide Labels

I was asked by the Museum Director to draft, record, and upload a series of audio guides for works in the permanent collection. Below is a link to the labels for these guides. The actual audio is accessible if you follow the instructions on them. This can be done from any type of phone.

“Snapshots” of works in the El Paso Museum of Art’s permanent collection

I was asked by the Director of the Museum to write up brief summaries of the most interesting aspects of some of the more important works in the collection. Ultimately these will be published on the EPMA’s new website in December of 2017.

“Snapshot” of Works in EPMA’s Collection

Ambrogio Lorenzetti (attributed to), Madonna and Child, c.1335-40

NYU conservator Diane Modestini has made a strong argument in favor of this being a true Lorenzetti. If so, it’s one of the very few outside of Italy. Ambrogio Lorenzetti is viewed as one of the most important Italian artists of the 1300s, and was a leading figure in Siena’s dominance of Italian art during that time. People in Siena loved their “bling” and this painting illustrates that with its stunningly rich and detailed depiction of embroidery on the Madonna’s gown and veil. It also reveals the use of red earth as a base for the gilding that we see in religious paintings from the 1100s to the 1400s. In this painting, the gold leaf has worn off and we can see the red underneath (also true for the flanking saints in the Giovanni di Paolo Assumption of the Virgin). Finally, and perhaps most significantly, the composition in which the Madonna’s cheek touches the Christ Child’s shows the increasing interest in the human emotions of holy figures.

Master of the Osservanza, Adoration of the Shepherds, c.1440

This is a jewel of a painting that’s a great example of a personal and portable altarpiece, in which the two outer wings are hinged and can be closed on top of the center panel. It’s also by a Siennese painter (or painters) and shows that love of rich color and gold leaf. However, it also illustrates the influence of an increasing interest in depicting natural settings as opposed to a solid gold leaf background. The identity of this particular artist has been much debated. It may be the work of a temporary company of artists, or of Sano di Pietro (who painted another one of the Kress’ Madonna and Child works).

One of the most fascinating things about this painting is the way its composition is similar to a graphic novel. On the top of the left wing is the angel Gabriel kneeling in front of Mary, who’s on the top of the right wing, reacting to seeing the angel and hearing the announcement of her holy pregnancy. In the center panel up at the top are shepherds reacting to the angel announcing the birth of Christ, and at the bottom, those same shepherds, with their dog, have come to see the baby Jesus. At the very top is the Last Judgement with the souls of the blessed on Christ’s right (viewer’s left) and the damned on Christ’s left. Together these scenes form the essential story of Christ.

Filippino Lippi, Saint Jerome in his Study, mid 1490s

Filippino Lippi was the son of a well-known Florentine painter, Filipo Lippi, who just happened to be a monk (Filippino’s mother was a nun). The elder Lippi taught Sandro Botticelli, who, in turn, taught the younger Lippi. This means EPMA has paintings by both the teacher (Botticelli) and pupil (the younger Lippi). By the time he painted Saint Jerome in his Study, Filippino was almost as sought after by patrons as his teacher.

St. Jerome was the name saint of Friar Girolamo (Jerome) Savonarola, who was a powerful figure in Florence during the 1490s. He preached passionate sermons on the need to reject luxury and act in a Christ like manner. He also encouraged personal devotion and identification with Christ and the saints through the contemplation of proper images that reflected the values of simplicity. The nephew of one of Filippino’s friends and patrons was an avid follower of Savonarola, so the artist may have done work for Savonarola supporters. The simple environment surrounding Jerome, and the way in which his contemplative figure is pushed to the front and framed by his desk, would have made it an excellent candidate for encouraging personal devotion. The Saint appears focused on his work of writing (Jerome is noted as having written the first version of the Bible in Latin) with no decorations or other people to distract him. Filippino’s interest in the detailed realism of artists in the Netherlands and Flanders is reflected in Jerome’s weathered face, and the objects that are in the room.

Sandro Botticelli and workshop, Madonna and Child, mid 1490s

One of the leading artists in Renaissance Florence, Sandro Botticelli is probably the most universally known artist in the Kress Collection. Most people are at least generally familiar with his painting Birth of Venus, which shows the goddess standing on a seashell and being blown to shore by a wind god. The face of the Madonna in EPMA’s painting bears a strong resemblance to the face of Venus, and other of Botticelli’s pictures of women. This probably results from the artist’s awareness of the ideal of beauty in Renaissance Italy, which included pale skin, thin, dark, eyebrows, a broad forehead, a long neck, small dimpled chin, and slender fingers.

This version of the Madonna and Child is from late in Botticelli’s career and indicates the influence of an increasing focus on personal devotion among many leading Florentines. The round or “tondo” shape was for domestic rather than church use, and the figure of Mary is dressed relatively simply, although still in fashionable clothing of the 1400s. In addition, there is little use of gold, and at least one conservator argued that the gold on Mary’s robe is a later addition. Finally, the composition pushes Mary and Christ to the forefront and focuses the viewer’s attention clearly on them. The tender way that Mary holds her son and his clinging to her veil was likely intended to encourage an emotional connection to the holy pair.

Lavinia Fontana, Christ with Symbols of the Passion, 1576

Lavinia Fontana, who lived and worked in Bologna, Italy, is one of the earliest documented female artists in Europe. She is also noteworthy because she was more successful than her father Prospero, also a painter, and became the breadwinner in her family, while her husband looked after the household. This is one of a few surviving works painted before her marriage. Her signature on the tablet at the front left side designates her as “Lavinia Fontana, virgin.” She created two versions of this painting (the other is in the collection of Rollins College) but EPMA’s is the original one.

This painting is a wonderful example of Fontana’s use of color, detailed depiction of nature, and focus on the emotional impact of religious scenes. The emotion is conveyed in the contrast of the children, probably intended to represent putti, or child angels, and the size and weight of the cross, column, and Christ’s body that they struggle to hold up. It also shows Fontana’s use of Mannerist style in the dramatic twist of Christ’s body, and the elongated proportion of the angel holding the cross. The symbols of the Passion include the cross, column on which Christ was whipped, nails (in the hand of one of the angels holding the column), whip, crown of thorns, sponge (below the cross), and the burial shroud.

Artemisia Gentileschi and studio, Saint Catherine of Alexandria, c.1630-35

Artemisia Gentileschi is probably the most well-known early female European artist. Among her achievements, she was the first female member of the Academy of Art and Design in Florence. Her father, Orazio, was a very successful painter, and fostered her training and career. Artemisia’s subject matter was often dramatic and bold, and broke the expected mold for female artists. This particular painting, however, shows the softer side of her work, and possibly the work of her daughter.

There is a marked difference in the technical skill evident in the painting of the head and neck, and the remainder of the figure, where the clothing, in particular, falls in an awkward way. This indicates two artists at work, one of whom appears to have been less experienced. We know that Artemisia did teach her daughter Prudentia, who would have been around 14 in 1632, so it’s likely that this painting of St. Catherine was a mother/daughter production. According to legend, St. Catherine considered herself married to Christ, and was tortured on the wheel and executed for her refusal to marry when ordered to do so by the Roman Emperor.

Bartolome Esteban Murillo, Ecce Homo, c.1672-78

Bartolome Esteban Murillo is one of the most famous Spanish painters. He dominated Spanish art in the mid to late 1600s and is one of the only painters of the period to have become known beyond Spain during his lifetime. He lived and worked in Seville, where he received major Church commissions, one of which may have included this painting. It was painted late in Murillo’s career and is characterized by the soft edges, diffused light, and sketchy brushwork that gave his artworks their soothing, gentle appearance. This style proved very popular in Seville by the late 1660s, and may have been viewed as an antidote to the increasingly difficult reality of life in the city during a period of severe economic decline.

Murillo painted several versions of the Ecce Homo (or Man of Sorrows). We know that as of 1786, this version was in the Chapel of the Virgin of Pilar in the Seville Cathedral. The text was added in 1838 when the painting was presented to King Louis Phillipe of France. In an interesting connection, Louis Phillipe’s father, Louis Phillipe II, Duc d’Orleans, was the last member of his family to own EPMA’s Education of Cupid by Lambert Sustris.

Hyacinthe Rigaud, A Magistrate of Requests, c.1702

In conversations with museum visitors, they will often remark that the gentleman in this portrait seems like someone they’d like to meet. Hyacinthe Rigaud was a highly successful portrait painter, in part due to his ability to give his paintings a sense of individuality and dignity. His most famous work is a full length portrait of King Louis XIV, which hung in the palace at Versailles. The royal portrait was widely praised, and Rigaud received commissions from several other members of the royal family.

The artist, however, gave the same attention and skill to his portraits of members of the upper middle class. This portrait is one of many that he painted of judicial officials who supported royal government at the local level. A Magistrate (or Master) of Requests was appointed to review any decisions of the local governing body that were appealed. Rigaud’s portraits of this type of official often included references to their work such as the book which the subject appears to have been reading. His authority as a representative of royal justice is emphasized by the velvet canopy over his head. Sitters would have been able to choose details such as these from examples in the artist’s studio.

Bernardo Bellotto, Entrance to a Palace, c. 1762-65

The “palace” pictured here never existed except in the mind of Bernardo Bellotto, whose expertise in painting architecture enabled him to create his own imagined building (a cappricio) that any viewer would assume to be an actual building. Bellotto’s expertise came in part from his study with his famous uncle, Giovanni Antonio Canal, or Canaletto. The signature on this painting reveals that the artist capitalized on his uncle’s reputation by signing it “Bernardo Bellotto de Canaletto.” By the time he painted this work, he was on the hunt for a new patron, and hoped the Polish Count Voivod Potocki could give him an introduction to the Polish court.

One can argue that, in some ways, Bellotto surpassed his teacher. When you look carefully at some of the architectural elements, such as the tops of the columns that run along the front of the palace, or the decorative sculptures, you can notice that the thickness of the paint application makes them actually three-dimensional. Another way in which Bellotto moved beyond Canaletto, at least in this painting, is his inclusion of ordinary people, even a beggar, alongside and equal in size to, Potocki, his son, and their servant, grouped on the left foreground. While we can’t be sure of the reason for Bellotto’s inclusion of the humble figures, it may be due to his experience of the social consequences of the Seven Years War, during which Dresden was heavily bombarded.

Gilbert Stuart, George Washington, n.d.

During his lifetime, Gilbert Stuart was the most famous portrait painter in America. He studied with the English painter Benjamin West from 1775-1780 and stayed in England until 1792. This meant that when he returned to America, he had the desirable factor of having been accepted as a portraitist by English society. He has the distinction of being one of only four American artists for whom President Washington posed (one of whom was Rembrandt Peale). EPMA’s version of the most famous of the portraits was commissioned by Richard Worsam Meade, Naval Agent to Spain under President James Madison.

Beginning in 1918, silver dollar notes bore an engraved version of Stuart’s portrait of Washington. As a consequence, most Americans have become extremely familiar with this image, but don’t necessarily know where it came from. Stuart’s portrait of Washington was so popular in his lifetime that he painted multiple versions of it (over 100), based on his original unfinished painting of 1795. The story goes that he was so pleased with the original that he left it unfinished in order to keep it as a model. According to Stuart, Washington was a very difficult sitter. He observed that, when posing, “An apathy seemed to seize him and a vacuity spread over his countenance, most appalling to paint.” No wonder he kept what he viewed as a good “take.”

Thomas Sully, Margaret H. Sanford and Portrait of John Sanford, 1830 (pair)

Thomas Sully was second only to Gilbert Stuart as the most sought-after American portraitist in the years following the Revolution. He was born in England but his family immigrated to Richmond, Va. when Sully was a boy, and he opened his first portrait studio there in 1804. He moved to Philadelphia in 1806, and arranged to study with Britain’s famous portrait painter Benjamin West in 1809. Sully’s mastery of rapid but delicate brushwork and use of light was flattering to his sitters, and allowed him to paint quickly.

The couple in these two portraits, were painted either shortly before or after their wedding on July 17, 1830. Margaret Halliday Sandford (1812-1860) was the daughter of a wealthy merchant in Fayetteville, N.C. John Sandford (1800-1870) moved to Fayetteville from Philadelphia in 1825 to work at a branch of the second Bank of the U.S.* Sully did travel for his profession, and so these may have been painted in North Carolina, but it’s equally possible that the couple spent time in Philadelphia, where John’s family was located, and had the portraits painted there. Sully’s approach emphasizes Margaret’s grace, but also her wealth, while John appears lively but a proper businessman.

Margaret was later remembered as follows (c.1880): “Mrs. Sandford was a model of refinement of manners and all wifely accomplishments, noted for the sweetness of her temper and unfailing cheerfulness of spirit.”

*I’ve added photographs of the Sandford House, the Halliday House, and the ballroom where the wedding celebration was held, to the object file.

Rembrandt Peale, Girl at a Window, 1846

Rembrandt Peale was the son of the successful American painter and naturalist Charles Wilson Peale. He studied with Benjamin West in England, and met the artist Jacques Louis David while in Paris, before settling in Philadelphia in 1831. The younger Peale excelled at painting idealized images inspired by neoclassical painters such as David. He was based in Philadelphia, but spent time in all of the major American cities, as well as those in Europe.

Girl at a Window is Peale’s version of Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting of the same name. In Peale’s painting, the young woman is the image of Victorian perfection, smoothly painted with rosy checks, large, dewy eyes, and hair with soft curls. His daughter Rosalba may have been the model. Peale was among many artists to have created versions of Girl at a Window, including Thomas Sully.

Edward Mitchell Bannister, Untitled Landscape, c.1883

This small painting is one of the more significant pieces in EPMA’s American collection, because it was painted by one of the first African-American artists to be recognized nationally. In 1876 Bannister’s large-scale painting, Under the Oaks (now lost) was awarded a first prize at the Philadelphia Centennial. According to his recollection, the jurors for the exhibition were quite shocked to realize that they’d awarded a prize to a black man, but his fellow artists defended the award and his skill.

Bannister was born in Cananda in 1828, and moved to the U.S. in the 1850s, where he worked as a barber and later became part of the Abolitionist movement. He married Christina Carteaux, a very successful society hair-dresser, and settled in Providence, Rhode Island, where she had connections. Bannister loved the natural world, and was drawn to the celebration of nature that he saw in the work of the French Barbizon School and early Impressionists. After capturing the award at the Centennial, he received numerous commissions for works which included biblical and mythological scenes, although he remains best known for his landscapes such as this one.

John Henry Twachtman, Twilight, n.d. (probably c. 1880-1893)

John H. Twachtman was one of the most innovative of the artists designated as American Impressionists. Twilight probably depicts a landscape on his Greenwich, Connecticut farm, which he bought in 1891. The stone wall that runs diagonally through the scene was typical of New England farms, and such walls frequently appear in Twachtman’s paintings from this period. This painting may have been exhibited at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, under the title Autumn Shadows.

He first studied art in Cincinnati, and then in Munich. The most significant impact on his work, however, was time in Europe from 1883-85, where he painted with Childe Hassam and Willard Metcalf, and saw paintings by James McNeil Whistler. Afterwards Twachtman’s brushwork became increasingly loose, with more muted colors. Art Historian Susan Larkin observed that “[Twachtman’s] lack of commercial success contributed to his artistic independence, freeing him from the temptation of producing saleable pictures according to a proven formula” and many of his paintings, such as this one, have an almost abstract quality.

Theodore Butler, Fireworks, Vernon Bridge, 1908

Theodore Earl Butler was born in Ohio and studied at the Art Students League in New York under William Merritt Chase. This painting may remind visitors of the work of Impressionist painter Claude Monet, and there’s a good reason for that. Like many of his fellow American artists, Butler traveled to France for further study. Unlike the other Americans, however, Butler settled in Giverny, France in 1888 and made it his permanent home. He met Monet very soon after reaching Giverny, formed a friendship, and cemented the relationship when he married Suzanne, Monet’s stepdaughter and favorite model in 1892. They likely often painted alongside each other, with Butler adopting Monet’s “plein aire” or “outdoors” method.

EPMA’s Fireworks, Vernon Bridge is one of two versions of the subject painted in the same year. The bridge is on the River Seine, and was built and destroyed multiple times. The version pictured here dates to 1872 and was destroyed in 1940 during WWII*. Interestingly, a mill on the bridge, dating to around 1400, has survived to the present (and is the subject of one of Monet’s paintings). If you look carefully at Fireworks, you can make out the roofline on the far right of the bridge. Butler’s pallet is similar to Monet’s, but his expressive brushstrokes and use of singular lines of vivid color, took his style beyond that of his stepfather-in-law and into the realm of the post-Impressionist Modern artists.

*I’ve added an image of a late 19th c. print showing the bridge, and a photograph if the mill to the object file.

Frederic Remington, The Mystery/A Sign of Friendship, 1909

Frederic Remington is the most widely known artist of the American West, although he lived most of his life in New York (President Theodore Roosevelt called him “one of the most typical American artists we have ever had”). This painting is one of Remington’s last works and was probably created just months before his death. It’s a strong example of two important aspects of his work, the influence of Impressionism, and his fascination with the Plains Tribes’ “superstition” regarding nature and its signs.

We don’t know exactly what Remington meant to depict here, but it was given the title The Mystery in a copyright filing in 1909, so perhaps the artist ultimately intended it to be uncertain. This uncertainty about what sign the Natives are seeing is underscored by the fact that they are facing the viewer, so what they are looking at remains for their eyes alone. Remington felt the pull of the West from an early age. In his “day job” as an illustrator for Harper’s Weekly, he often travelled west, where he made his sketches and took photographs, but completed the work in his New York studio using props and models. By the early 1900s, his paintings show the clear influence of Impressionism, with its focus on loose brushwork, a light color palette, and soft edges. The frame is probably original and designed by Remington.

Robert Henri, Carl (Boy in Blue Overalls), 1921

This portrait of Carl Schleicher was probably painted in the artist’s studio in Woodstock, N.Y. and is one of at least three paintings of Carl. During the 1920s Henri painted many portraits of children, although the majority of them were created during his summers in Ireland. EPMA’s version of Carl shows Henri’s characteristic elements of strong color contrast, generally dark palette, and vigorous brushwork. Some critics have viewed Henri’s later works, such as this one, as a triumph of sentimentality over the views of gritty urban life that gave Henri and his friends the title of the “Ashcan School” of painters.

Robert Henri was actually born Robert Henry Cozad, but the family changed their name and moved to New Jersey after Henri’s father shot and killed a man during an argument. Henri studied art in Paris, as did so many of his peers, but by 1891 Henri was in Philadelphia, where he became part of the “Philadelphia Four” with William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan. The four all moved to New York City in the early 1900s. By that time, Henri had rejected what he viewed as the decorative and ethereal nature of Impressionism in favor of an artistic approach that, like journalism, was concerned with recording “real life” in all of its dirty splendor. Henri forged his own artistic path and rejected all attempts to impose barriers on art. As his contemporary and radical thinker Emma Goldman said, Henri was “an anarchist in his conception of art and its relation to life.”

Childe Hassam, Still Life with Peaches and Old Glass, 1922

Before studying in Paris in the 1880s, Childe Hassam painted in a realist style. After Paris, where he probably crossed paths with Robert Henri, Hassam became a “pioneer of American Impressionism,” with its visible brushstrokes and often “sketchy” quality. In addition to the physical characteristics of Impressionist artwork, Hassam supported their focus on painting the world around them. He declared, “I believe the man who will go down in posterity is the man who paints his own time and the scenes of everyday life around him.” For Hassam, however, who summered in the Hamptons, the life around him was largely the life of privilege, reflected in the fine glass and buffet table in the EPMA still life.

This still life also shows strong influence from Modern artists such as Cezanne and Matisse. Cezanne’s work was exhibited in New York as early as 1910, and at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1921, so it’s entirely possible that Hassam was inspired by his approach to painting. Certainly the use of thick brushstrokes, slightly tilted perspective of the buffet’s surface, and careful gradation of color to give shape to the peaches, are also characteristic of Cezanne’s style. The painting was reframed by EPMA with a custom-made frame in the style favored by Hassam, who designed his own frames.

Audley Dean Nicols, View of El Paso at Sunset, 1922

This painting has been the subject of many arguments among El Pasoans about its viewpoint and the identity of buildings depicted in it. No evidence has turned up that would definitively solve the puzzle, although one researcher in 1972 declared that the vantage point is from Montana and Trowbridge. Regardless of the specific identities of the buildings shown, Nicols clearly illustrates the contrast between the wild desert, and the increasingly industrial city, where several smelters and other factories operated, largely in the central and southern sections. This view of a dynamic city may have been exactly what the heads of the First National Bank of El Paso, who commissioned the painting, wanted.

View of El Paso at Sunset contains all the elements of a classic Southwestern landscape. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, many eastern artists travelled west, including Nicols, who was from Pennsylvania, and were enchanted by the striking landscape. The strong horizontal lines, clear bright sky, sharp shadows, and color contrasts, provided artists with an ideal inspiration for their work. Desert landscapes were also characterized by unexpected color, and led Nicols and some fellow landscape artists to be dubbed “the purple mountain painters.”

Max Weber, Still Life with Flowers, 1936

It’s possible that Max Weber painted this still life while listening to Bach. According to his daughter, Joy, he believed that listening to music while painting made him work better. Weber was born in Russia, but moved to Brooklyn, N.Y. at age 10. He studied in Paris from 1905-1909, where he became enthusiastic about pre-Cubist works by Matisse, Monet, and Cezanne. He studied with Matisse, and met Albert Gleizes, Robert Delaunay, and Picasso. Back in New York, he helped introduce the cubist style, but by the 1920s his own work had become more representational, as evident in Still Life with Flowers.

Despite being clearly identifiable, the flowers, vase, and table, have many qualities associated with the French Modern artists, such as flatness, an emphasis on outline, tilted perspective, and the use of intense colors. Weber’s artistic goal may have been to reveal the “essence” of the flowers. In an essay published in 1916 he observed, “I live the flowers, their color and fragrance…The flower is not satisfied to be merely a flower in light and space and temperature. It wants to be a flower in us, in our soul.” The frame on this painting is a reproduction in the style of Weber’s original design. It was successful enough to prompt a note of appreciation from Joy Weber.

Tom Lea, Untitled Mural, 1933

Tom Lea was and is one of El Paso’s most noted and beloved artists. Lea studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, assisted the muralist John Warner Norton, and then spent a year in Italy.

He painted this mural in the breakfast room of his family home when he was 22*, to amuse his 6 year old brother Dick, and to pass the time while he and his wife waited for their house in Santa Fe to be completed. When it was donated by the owner of the house at the time, it had to be carefully removed from the room’s wall and attached to its current support. Lea later referred to it in an interview as a “cartoon painting” and, like a cartoon, it illustrates the story of the Southwest, with specific references of significance to the Lea family.

It “reads” from left to right, beginning with the ancient civilization of the Cliff Dwellers, and the origins of the tradition of native pottery, which the Lea family collected. In the center is corn cultivation and a free-standing adobe house of the settlement period, and it ends with a cowboy chasing a steer. According to Lea, the center and far right also depict Mimbres Hot Springs in New Mexico, where the Leas often vacationed, while the rider and his horse portrays Lawrence Cooper, the owner of the place they stayed when in New Mexico. His mother was apparently not amused by the inclusion of an outhouse with an open door (next to the adobe house). Lea included the roadrunner because the bird “fascinated” his little brother.

*The object file contains photos of the mural in situ and of its removal.

Luis Jimenez, Barfly~Statue of Liberty, 1969-1974

Luis Jimenez is probably El Paso’s most nationally-known artist. He was born in El Paso, and assisted his father in his sign shop, where he learned to work with metal and neon, and was drawn to the bright and “over-the-top” nature of advertising images. Barfly~Statue of Liberty shows this influence with its use of glittering fiberglass and Liberty’s exaggerated figure. Jimenez, however, was also passionate about the need to address social issues, particularly during the turbulence of the late 60s and early 70s. Speaking of this sculpture he said, “This was a very conscious attempt to make a social commentary about what I felt was going on with the country…I grew up with a fairly strict moral code…so I thought of someone who was a barfly as someone who was trying to go to hell or something.” This accounts for Liberty’s raised beer glass, tipsy posture, and short skirt.

Jimenez studied at UTEP, and moved to New York after graduation, where he had his first solo exhibition in 1969. By 1972 he was back in El Paso, and became known for fiberglass sculptures that often focused on Southwestern stereotypes. In his hands, however, the stereotypes became larger-than-life and celebratory. Rudolfo Anaya, former professor of History at the University of New Mexico, said of his work, “It was first called outlandish and garish, but it spoke not only to Hispanics, but to the world.” Jimenez’ work is featured in the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Self-Portrait with Calavera, 1996

In addition to his fiberglass sculptures, Jimenez created a number of lithographs, such as this one. This portrait of himself, essentially as a skull, echoes an earlier self-portrait of the artist as a wolf (1985). In both cases, his blind eye, the ultimate result of a childhood BB gun accident, is prominent, and identifies the artist as the subject beneath both the skull and the wolf. There is an energy in Self-Portrait with Calavera that results from the strong, squiggled lines, although this energy is tempered by the hollowness of the eyes. The 1980s and 90s were difficult years for Jimenez as he struggled with his health, his marriage, and completion of the monumental sculpture commission of a rearing horse for the Denver International Airport. The airport commission ultimately killed him in 2006, when a portion of it came loose from a hoist and cut his femoral artery.

Manuel Acosta, Doña Josefa, n.d.

Manual Acosta was born in Mexico, but grew up in El Paso, where he graduated from Bowie High School. He studied at the College of Mines and Metallurgy (now UTEP) as well as UC-Santa Barbara. After Acosta returned to El Paso from California, his former teacher, sculptor Urbici Soler, connected him with artist Peter Hurd, who needed an assistant. Hurd encouraged him to paint what he knew best and to draw on his Mexican-American heritage. Acosta’s success in following this advice is evident in this portrait of Doña Josefa. Details such as the ribbon in her hair, her fine blouse, the bible on the table beside her, and the stark desert background, combine with her weathered face to make us wonder about her character and her life. The spare color palette, and precise lines of the portrait also suggest the possible influence of Andrew Wyeth, whose daughter, Henrietta, was married to Peter Hurd.

James Drake, Cinco de Mayo, 1988-1989

This combination of sculpture and charcoal drawing both fascinates and puzzles many Museum visitors. There are several reasons for this. The use of charcoal along with a heavy steel frame, and sheer size, makes Drake’s reimagining of 19th century artist Francisco Goya’s 3rd of May, 1808 very dramatic. The steel train at its base adds further drama, but also makes us wonder how it’s connected to the image above it. In any interview given in 2005, Drake connected the train and Goya’s image of the violence of war with the 1987 death of 17 Mexicans who were abandoned in a boxcar by the “coyote” who brought them across the border. He specified that the locomotive was intended “to tie the two events together.” There is also a connection between the 3rd of May in Spain, and the 5th of May in Mexico. Both of these events, the mass executions of Spanish who resisted the French invasion, and the unlikely victory of a Mexican force over the larger French invading force on Cinco de Mayo, became sources of inspiration for the successful expulsion of the French from Spain and Mexico respectively.

James Drake works in a variety of media, including sculpture, drawing, painting, and video. He received a BFA and MFA from the Art Center, College of Design in L.A. His work blends his inspiration from art “masters” such as Goya, with contemporary materials and approaches.

Gaspar Enriquez, Color Harmony en la Esquina, 1992

El Paso Artist Gaspar Enriquez created this monumental couple as part of a commission for the San Antonio Convention Center. The title of the piece refers to Enriquez’ observation that in the Segundo Barrio neighborhood of south El Paso, young people would hang out on the corners with no prejudice or animosity. Although both members of the pair in this piece are Hispanic, in the second pair of the commission, one is Black and the other Hispanic. The artist said that he wanted to send the message that “we could all get along together.” The impact of the scale of these young people, both of whom were students at Bowie High School, also lends dignity to them as residents of the second oldest neighborhood in the city.

Enriquez earned a degree in Art at UTEP, and an MA in Metalsmithing at New Mexico State. His art has focused largely portraying the complexity of Chicano identity, particularly those often dismissed as trouble-makers and gang members. Recently, in the De Puro Corozan (Pure Heart) series, Enriquez has created portraits of his artist friends that capture the passion they give to their art. One of these was selected in 2016 for the prestigious triennial Outwin Portrait Competition and Exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. Enriquez taught art at Bowie for over 30 years, and many of his students have become successful artists.

Vincent Valdez, Pride of the Southside, 2005

This pastel is a favorite with visiting school groups, drawn by its intense colors and subject matter. Vincent Valdez was born and raised in the southside neighborhood of San Antonio, and in a c.2005 video interview, commented that “all the work I’m creating today is very derivative of that community.” The theme of the boxer dominated Valdez’ work between 2003 and 2005, and, according to video interview, the artist was “trying to tap into the idea of recreating the hero” as representing the individual who persists through difficulties, “not letting fear get in the way.” Valdez admits that ultimately the boxer began to be a type of self-portrait. Pride of the Southside suggests this aspect by setting the boxer in the artist’s boyhood community. The figure also expresses Valdez’ interest in portraying the tension of duality, in this case someone caught “between surrender and hope.”

Valdez began his art career at a young age, when he spent summers assisting San Antonio muralist Alex Rubio. He later earned a BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design on a full scholarship, and was the youngest artist to receive a solo exhibition at the McNay Museum of Art. Valdez’ work has been shown at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, and the National Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago, among others. His more recent work, The Strangest Fruit series (2013) and The City (2016) are more overtly political than his earlier work, and explore racial tensions in America.

Link to The Art of Boxing video (2005)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGy9Lwteygo

Chalking the Museum at Chalk the Block Festival

As part of the El Paso Museum of Art’s first time participating in El Paso’s Chalk the Block art festival, we invited visitors to “chalk the museum” and leave their own artwork. Overheard during the activity, mom to daughter, “You saw the artwork in the museum and now you have your art on the museum.” Click on the link below for photos of their creations. You can also see our activities inside the museum.

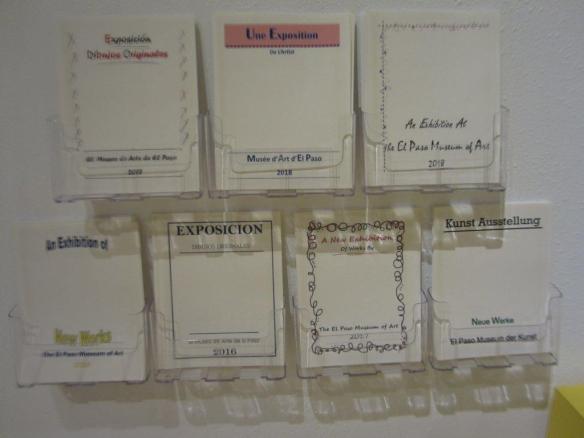

In-Gallery Activity for Posting Picasso Exhibit

These are photographs of the “Make your own Branded Poster” activity that I developed for an exhibit of Picasso posters at the El Paso Museum of Art. I designed the poster templates to resemble the aesthetic of the posters in the exhibit. It’s proven quite popular.